Talking peace and media in South Asia

Whenever people from India and Pakistan meet, it’s like a reunion of long-lost college friends. Excitement runs high, and voices are raised a pitch higher out of sheer happiness at seeing the other after ages. As a young peace activist, I enjoy watching this camaraderie, which is visible also in countless online webinars between peace makers on both sides.

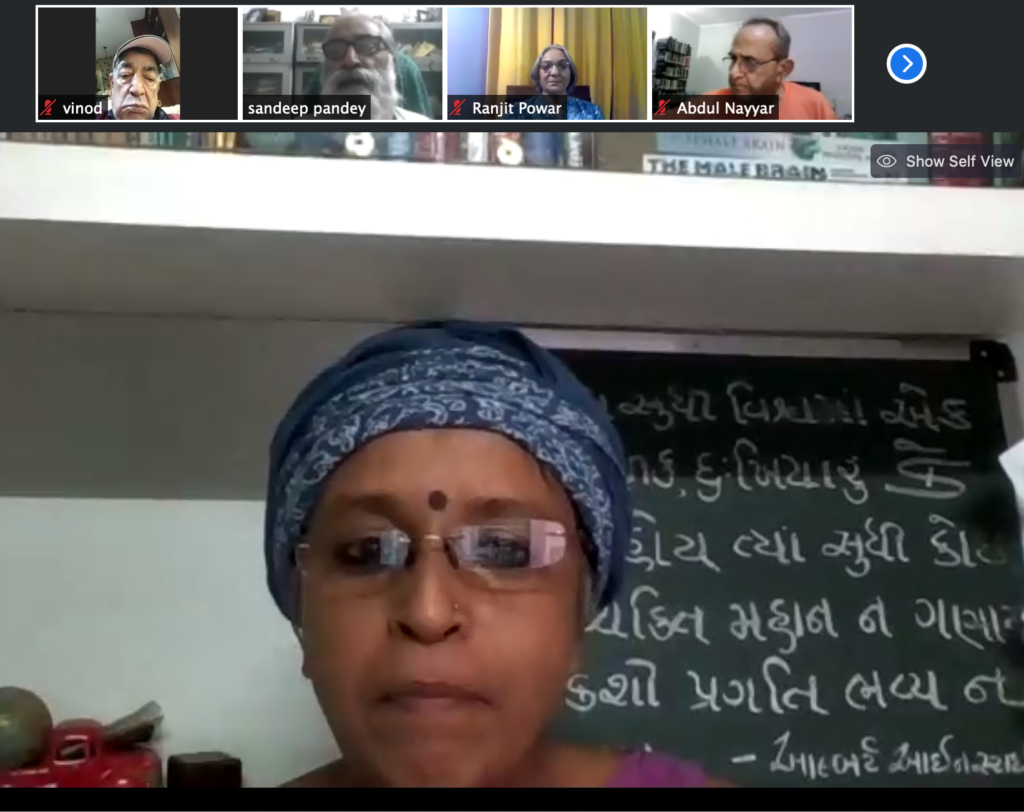

At one such webinar last Sunday, October 18, 2020, I observed enthusiastic personal greetings between veteran peace activists on both sides of the India Pakistan divide as participants acknowledged each other’s presence, asked about family members and assessed who’s missing from the party.

“Neighbourhood hasn’t changed since I last saw you”, someone quipped. Everyone burst out laughing at the inside joke referring to the perennial issues between and within India and Pakistan.

Titled “Media and Peace in South Asia” the event was organised by the newly launched youth group of the Pakistan-India Youth Forum for Peace and Democracy. Veteran activists Dr A.H. Nayyar in Lahore and Sandeep Pandey in Lucknow jointly moderated the event, a task assigned originally to another senior activist Syeda Diep, who was only able to join later due to a family illness.

Featured speakers were media seniors Jawed Naqvi, the Delhi-based journalist with a regular column in daily Dawn, Pakistan, and Prof. Mehdi Hasan, professor of Journalism and Mass communication at the Beaconhouse National University, Lahore, who shared their views about the role of media and its contribution towards peace and harmony.

Prof. Hasan began by looking inwards, saying that while he was not that familiar with Indian media, he found the Pakistani media’s “ravaiyya” (attitude) quite stereotypical. In this era of general whataboutery, it was refreshing to hear someone focus within with integrity. I wondered how many Indian media experts were capable of similar introspection.

History lessons

To add to his point about the Pakistani media behaving regressively, as it has in the past, Dr Hasan shared a story from 1962, when he had just joined MA classes and was invited to do radio commentary. He was a bit hesitant as he had zilch idea of the bilateral situation. The producers told him: “10 minute ka programme hai bas India ko bura bhala kehna hai” (you just need to criticize India in the 10 minutes programme). The pay, Rs. 10 a sitting, was generous in those days. He admitted to doing many such programmes and reflected that things have changed little since then.

The same modus operandi is visible today, he said. There is a lack of inquiry or the kind of probing, research that media is supposed to do. Our history is distorted, things are stuck there, and the media are playing an active role in this, said Dr Hasan. Pakistani media “apne mulk ki har khaami ko India par daal deta hai aur sochte hain ki unka farz ata ho gaya” (blame own country’s every fault on India and thinks they have done their duty).

Picking up the thread, Jawed Naqvi argued that not all media are negative. He cited his own experience with a Pakistani newspaper, which he takes the risk of writing for because they share similar thoughts.

He began a crash course on the background of media with a precursor for all us young peace activists. For starters, he asked us not to focus on being “typewriter guerillas” but keep an eye on the proprietors. “All industries are run by its owners, and media is no different. The way we are connected today via Zoom, he pointed out, that connection can just as easily be severed by its proprietor”.

Jawed Naqvi shared an interesting vignette from the 1857 war of independence against the British, when fliers with messages were an early form of media. People would post them on walls in cities and villages, or give them to the village head to read out at public meetings.

Talking about his association with Reuters, he went into the history of the news service which had humble beginnings as an organisation that connected markets through homing pigeons. As technology improved, news travelled faster. When Gandhi was assassinated in January 1948, the news reached London within minutes.

Compare this to earlier times, like when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, 1865. The news went via a ship to Europe taking approximately 12 days. However, just before the ship docked at Liverpool, a trader on the ship released a homing pigeon to his office. On receiving the message, his office staff sold all the shares of American railroads and other industries they were holding, helping the trader rake billions from the transaction! This was a new kind of news, based on benefits derived through the market.

Media responsibility

When the Rwanda massacre took place in the mid-1990s, the world seem unbothered, despite the perpetrators openly declaring the daily target of killing. For a very long time, the number of dead persons dispassionately appeared each day under the weather column, equating the numbers indifferently like degrees of temperature. One day a reporter from the massacre site reported that the coffee crop is devastated because the farm labourers have fleed to escape the violence, as their leader had been murdered. With the realisation that the coffee crop could be affected by this ongoing violence, alarm bells rang at New York Stock Exchange. This is what finally caught the attention of the media.

These stories display a hard fact about the news media: The shelf life of a story is growing shorter. Besides, “if it can move emotions but not markets, media is unlikely to be interested in it”, asserted Jawed Naqvi.

This reflects on the media ownership in India, he commented. Initially the Birlas – who loved Gandhi but disliked Nehru’s socialism — owned the leading media and set the narrative. Today, various companies owned by the Ambanis – whose business interests favour affiliations with the BJP — have stakes in multiple media houses. “Kabza kar liya hai poonjipatiyon ne. Ye maalik hain, ye use chalaate hain. Media ko jyada ilzaam na dein, aur na hi zimmedaari dein” (The capitalists have captured the media. They are the owners, they run it. Don’t blame the media too much, nor give them all the responsibility), concluded Jawed Naqvi.

Prof. Hasan had a difference of opinion: “Pakistan mein editors aur senior journalists ki gatekeeping bahut shiddat se zaroorat mehsoos hoti hai.” (In Pakistan we feel a dire need for the gatekeeping that editors and senior journalists do), he commented, discussing the possibility of dissent by media editors with a spine towards the proprietors and how it can bring about change. He stressed that the active role of journalist unions in opposing the proprietors shouldn’t be discounted either. He also mentioned how the English media, whose character is quite disparate to the Urdu media, is not as influential in Pakistan, and does not control the narrative substantially: “English aur Urdu media ka character bahut mukhtalif hai. Our journalism is a He says-She says journalism. There is no scope for investigation, and no resources invested on it.”

Aman Ki Asha

Several other activists shared their thoughts. Beena Sarwar talked about how the Aman ki Asha (hope for peace) initiative began, a kind of joint corporate social responsibility project between the Times of India and the Jang Group of Pakistan. Its launch in 2010 helped change the narrative. At that time, PIPFPD (Pakistan India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy) joint conventions had also not taken place for several years, so there was a huge vacuum.

It’s quite clear that people on both sides keenly want peace and good relations between both countries. When Aman Ki Asha was launched, there was a great response particularly from the young generation on both sides. Many formed their own organisation to further the peace narrative. But there are dangers associated with such peace activism.

For Pakistani activists, March 2014 was a turning point, after the murderous attack on Hamid Mir of the Jang Group following which the entire media outlet came under attack, including its Aman Ki Asha project.

Basically, anyone working for peace with India is periodically accused of treason, she said. One activist, not even affiliated with Aman Ki Asha except peripherally, forcibly disappeared. Recovered after seven months, he has since taken asylum in Sweden.

“On both sides of the border, peacemongers are publically and frequently referred to as agents of the other. The people who attack us have entire armies to disrupt the narrative. These dangers often distract us, as we end up focussing our energies on trying to save ourselves. We are up against A LOT, yet we need to continue our work, taking baby steps!”

Regarding journalism, she stressed the need for those with any kind of public platform to follow a code of conduct and ethics, including social media users. Everyone making public posts should follow journalistic ethics. “Gaali galauj na karein. Poochein toh doosre side ki rai, unhein sunein toh sahi, in terms of reporting. Tu tu main main na paR jayein.” (Refrain from being abusive and getting personal. Acknowledge the opinion of the other side, don’t get into petty arguments).

Peace park

Mohammad Ayyaz, a Pakistani-origin Rotarian in London, shared about the Indus Peace Park, a project he is working on with Indian-origin Rotarian Tony Sharma. This is a good example of how overseas Indians and Pakistanis can make a difference in the peace process.

Others at the seminar shared poetry and warm sentiments. From their farm in Gujarat, former navy chief Ramu Ramdas and his peace activist Lalita Ramdas lent their wholehearted support as elders who are “young at heart”.

“Peace between India and Pakistan makes good environmental sense also”, commented co-host Sandeep Pandey in Lucknow.

Talking about the Indus Water Treaty, environmentalist Dr Mansee Bhargava noted that both theoretically and practically, “it has proven to be the best treaty world over, withstood all kinds of turmoil”. She suggested using the IWT “as a base to connect people”.

“Climate change is not bound by borders but affects everyone equally. It is high time we reject anthropocentric solutions and place primary importance on ecology and the environment instead”, she added. “We need to put our heads together to solve problems which are the same on both sides of the border. This will in turn reward us by bringing us together”.

The next online seminar organized by this group will be on environmental issues in India and Pakistan.

Pragya Narang is a Delhi-based communications consultant and peace activist. She was drawn to the cause of India-Pakistan peace while traveling in Europe where she met Pakistanis for the first time. She found cultural affinity with them and realised they were different from the media stereotype. Twitter @pragyanarang. Email [email protected]