By Saleem H. Ali

US President Trump’s South Asia policy speech in August was more measured than his usual diatribe but he missed an important logical policy initiative. Noting Pakistan as a hindrance to the Afghan peace process, he mildly acknowledged that “Pakistan and India are two nuclear-armed states whose tense relations threaten to spiral into conflict.”

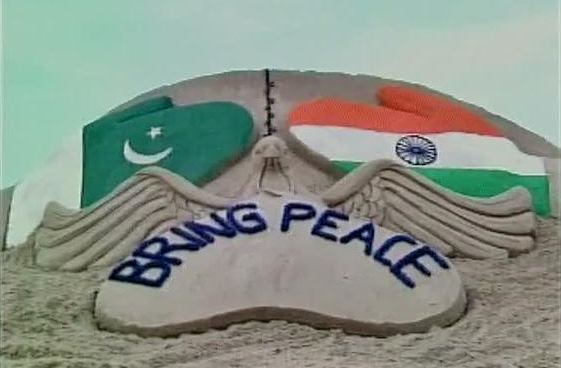

The logical next step would have been to ask if tense relations between India and Pakistan are the reason for the proxy conflict being played in Afghanistan. When this causality is evident, why can’t the United States invest more political capital to build peace between these two acrimonious neighbors?

The usual response from the Washington punditry is either that “India would never accept mediation”; or that “Pakistan is interfering in the internal affairs of India and should focus on its own internal conflicts.”

Such diplomatic defeatism enables the security establishments on both sides to perpetuate the status quo at the expense of US security interests and realizing the full economic potential of regional cooperation for their own people. It would be naive to think that with the level of trust deficit that exists at present, any peace process could bilaterally be successful between the two countries. Mediation is essential whether overt or covert, and the two countries which have the most leverage in this regard are the United States and China.

There has not been any serious attempt at a regional peace process between India and Pakistan at all. Only specific tension diffusion processes have been carried out such as the efforts by former UK commonwealth secretary Duncan Sandys (erstwhile UK Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations and Colonies) in the 1960s and the tepid efforts at conflict management rather than resolution by well-intentioned security diplomats such Richard Armitage during the Bush Administration.

India is concerned that any attempt at peace-building is often framed through the lens of the Kashmir conflict, which has highly divergent historical narratives for its Hindu and Muslim populations. Thus India feels a fear of national unraveling if the status quo on Kashmir would be disturbed. There is an immediate reference to Pakistan’s own secessionist challenges in Balochistan and the blame game between the two countries on mutual interference goes on ad nauseum.

To break this destructive cycle of narcissistic victimhood and neighborly recrimination, a regional peace process is needed which brings forth all aspects of postcolonial demarcation conflicts across the subcontinent. There should also be peace-building in the Pak-Bangladesh context which has led to a political paralysis between the Pro-Indian and Pro-Pakistani factions within the country. The United Kingdom, as the former colonial power that managed the Partition, has a historical responsibility to assist in this process, but the United States and China will need to invest the most political capital due to their concomitant influence.

The United States has more leverage with India and China has more leverage with Pakistan. An effort to build a strategic partnership on South Asian conflict resolution between China and the United States has value for both countries. China’s $65 billion investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) can only reach its full potential if there is security in Balochistan and the transport corridor across Pakistan.

The United States’ foreign direct investment in India is highly vulnerable without regional peace as well. Recall how hostility between India and Pakistan has earlier on led to American multinationals such as GE crying foul and threatening to dis–invest. Peace is indeed in the interest business leaders as well, which I am sure the Trump administration appreciates all too well.

Along with many Indian and Pakistani scholars, earlier on I have argued for science diplomacy and hydrodiplomacy between India and Pakistan in various ways. However, it is time to raise cooperative narratives from such “low politics” issues to “high politics” of war and peace.

An easy win for the broader South Asian regional peace effort could be an initial focused effort at resolving the Siachen glacier conflict between India and Pakistan, that a range of policy scholars, environmental scientists and even army generals have presented solutions for. However, this must be packaged within the broader regional peace effort or else it will be laughed at by the security hawks on both sides of the border.

US Ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, trusted her gut instincts when she made a sincere and admirable statement soon after assuming office in April of this year that the United States “very much wants to see how we deescalate any sort of conflict (between India and Pakistan) going forward.” However, the jaded old-timers at the State department criticised her and capitulated to the stale bilateral narrative which has borne no fruit for seven decades.

India and Pakistan are both utterly impoverished countries accounting for nearly half of the world’s “multidimensional poverty”. Despite their nuclear ascendancybravado and high-tech startups, they face a bleak future if they do not invest their precious resources in development rather than conflict.

The international community cannot just wait for these two nuclear powers to “sort things out.” Just as the Carter administration played a pivotal role in the detente between Egypt and Israel, the Trump administration can do so between India and Pakistan.

This is a pragmatic and not idealistic approach that requires diplomatic leadership and an entrenched and persistent capacity to endure rebuke and even ridicule. Ultimately, such a peace process is not only in South Asia’s security interest, it is very much in the security interest of the United States and its allies.

The writer is Distinguished Professor of Geography, University of Delaware and Affiliate Professor, University of Queensland, Australia. This is a slightly edited version of his piece in the Huffington Post. Twitter @Saleem_Ali